Archival Hauntings: The Strange Phenomenon of Co-Witnessing Memory

Kerry Backes joined Primary Collections in August 2025 as the first Graduate Intern recruited through the Department of Higher Education’s Presidential Youth Economic Stimulus Initiative. In 2025 she completed her Postgraduate Diploma in Library and Information Studies in the UCT Department of Knowledge and Information Studies.

Before beginning my internship, I held a romantic idea of what an archive would be like. The archive in my mind had been planted by stories. And so, to me the archive of my imagination existed in a basement, which smelt of aged wooden shelves and dust, or leather bindings. I had no real sense of the scale or diversity of archival material, especially the architectural and oversized collections, held by UCT or their individual needs. My true introduction to archival work began with a graduate internship at Deneb House, in the midst of the recovery effort. It was nothing like the imagined archive I had carried with me. And the work was often less glamorous than I had envisioned, but the materials themselves lived up to my romantic ideas and superseded them. Each item had a voice of its own, shaped by its creator and its history, and it did not need embellishment or a fabricated narrative to give it meaning. Realising this has had a lasting impact on me as I came to understand that while archive work was different from what I imagined, the value of the material and role of archivists was far more important as well.

Co-Witnessing Memory

During my internship, I was warned that the re-boxing process would take time. The materials damaged by fire, water, mould, and rust had to be individually assessed, cleaned, and rehoused in archival-quality boxes. And of course, I won’t elaborate on the importance of the re-boxing process itself; as the conservation team has already explained it far better than I could. Except to say that for those working on the re-boxing, it is a slow and meticulous process. Yet, what Deidre Goslett, the senior archivist in charge of the re-boxing warned me about was that it would also be distracting...

Every box held fragments of identity: letters, photographs, certificates, and newspapers that mapped out whole lives. As I handled folders on historians, unions, and community leaders, I began to feel something uncanny; an emotional connection to people I had never met. Reading their letters in sequence, I had insight into their lives and their memories, in the order that they had experienced them, sometimes from hope to failure, and I resonated with their experiences and memories. And while I find a similar connection with books, the difference was that these weren’t fictional characters, they were real people, and I felt a sense of personal connection and duty as a holder of their memory.

It was then that I began to joke about “the ghosts.” It’s the peculiar feeling that arises when you read a personal letter: the sense that its author, in some small way, acknowledges you. The archive, in this sense, becomes personified; and the memories it holds are inherited by those who work within it.

Archival Hauntings: The relationship between Archivists and Material

Curious about this experience, I came across a study titled “Humans and Records Are Entangled: Empathic Engagement and Emotional Response in Archivists” by Regehr, Duff, Aton, and Sato (2022). The authors describe archivists as “co-witnesses” to the lives contained within records - individuals who can be profoundly affected by the stories they preserve, especially when those stories involve suffering, resilience, or loss.

Reading their findings, I realised that my “ghosts” were not imaginary at all. They were living memory and an emotional response to co-witnessing the lives of people I had never met or known. To co-witness memory is to become a carrier of it, much like carrying the memories of our own families, where archivists can ensure that the lives of others are not forgotten or silenced by time. Experiencing this reminded me why heritage work matters so much. As I believe that anyone who has felt that connection to memory would understand the true value of museums, galleries, and archives.

Connecting With the Physical as well as the Metaphorical

The Jagger Library fire was a tragedy of which we as a university and society have not yet truly realised, and it has undoubtably transformed the landscape of South African archival work for years to come. But in some small ways, there is also light at the end of the tunnel. The recovery process, especially the re-boxing and audit, has allowed a new generation of archivists, interns, and volunteers to encounter collections that were once overlooked due to priority of heavily used material, inaccessible or thought to be lost in the Jagger fire. And at this point, before speaking about new connections to materials, I must mention that the senior archivists are so deeply connected to the physical material that they work with, that it feels nearly impossible to catch up.

Whether I am referring to Deidre Goslett, who can recount the collection number of any collection based on its name, or contents, or Isaac Ntabankulu who figuratively holds the architectural collections in his hands, and has literally held every architectural drawing belonging to UCT and the archive, in his hands, for organisation, reconciliation and repair. Isaac tells stories about the history of buildings, landscapes and architects as though he had dinner with them the night before, with a familiarity and depth of knowledge that is hard to understand unless you are aware of the connection which archivists have with the materials that they preserve.

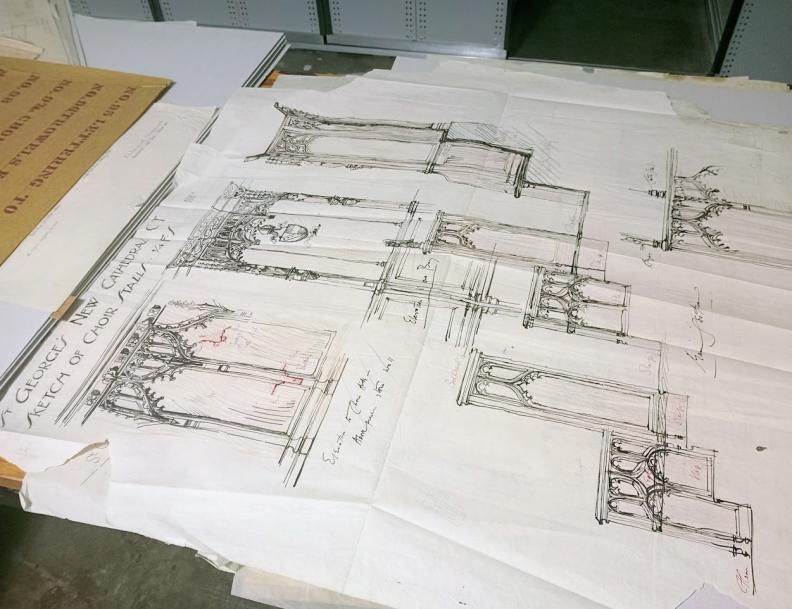

Like old friends drifting apart, some records disappeared from view, at the Jagger and throughout the recovery; lost amid relocations, prioritisation of heavily requested material, or the trauma of the fire itself. But through the recovery process, many of these collections have found their way back into the light. Among them are the drawings and plans of the Churches of the Province, a collection which contains some of the works of Sir Herbert Baker and St Georges Cathedral. Some of the drawings are even life-sized depictions of cathedral doors and windows.

A Living Archive

The Jagger recovery has reconnected lost materials and, in doing so, it strengthened the bridge between the archive and memory. As an intern, this work and experience have been an initiation into heritage work and living memory. However, it has greater relevance in showing discovery through loss, and the value of heritage work in connecting material to memory.

And in conclusion perhaps the archive is haunted after all. Not by ghosts, but by memory.

Source:

Regehr, C., Duff, W., Aton, H. et al. “Humans and records are entangled”: empathic engagement and emotional response in archivists. Arch Sci 22, 563–583 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-022-09392-5