Recovering the Archive

This is the picture I was taking at the time David Harrison’s photograph was captured. It depicts the entrance to the Reading Room. The gutted Archives Office is visible on the upper level. To the lower left of the entrance the remnants of the microfilm reader can be seen.

First Responders

"Good news. The basements are intact. Can you come on site now to show the technical team around?”- I leapt into my car and made the longest drive to work.

This was how the Salvage started for me, on the morning of Tuesday 20 April, only two days after the fire that gutted the Jagger Library. We had, until that moment, feared the worst. Only the day before, we had provided a comprehensive report of everything that was in the Jagger Library to facilitate the Vice Chancellor with reporting on the full scope of losses. As early as 19 April, based on this initial report, Nature magazine reported that “the losses were total”. These early reports were based on the intensity of the fire in duration and ferocity; they were made while the embers of the fire were still fading. Only a day later, when the fire was finally out, and the site was handed over to Isipani Construction, were we able to inspect the damage.

It was a miracle that the basements had survived the fires. I reported to the Mail & Guardian on that first day that the losses were less than expected, but that, since the fire, we hadn’t been able to check. Since this time, it has been clear that these seemingly contradictory narratives in the media resulted in significant distress among scholars and other stakeholders. So, I wanted to put this into perspective.

Not all was lost.

Contrary to public speculation, its important to note that the basement was not ‘fire-proof’. Indeed, the fire system in place had prevented the fire from spreading to the Chancellor Oppenheimer Library, but the reason the fire did not penetrate the basement, according to the fire inspector, was because the fire had run out of anything to fuel its carnage beyond the glass doors leading down the ramps into the basements. Had we cluttered that area with trolleys of books (which we do not do, for this specific reason), the destruction would have been far greater. Having said that, without the fire door in place, the fire would certainly have spread into the university’s main library, and potentially to the adjacent buildings, including the Sarah Baartman Hall.

In pitch black darkness, guided only by cell phone flash-lights, we proceeded down the ramp. When I felt the cold wet feeling rush up my legs it took me a moment to realize that the basement was flooded halfway up the ramp. At the lowest point, a full grown man would have been waist deep in the water.

I think I screamed. And then we mobilised, quickly.

Arrangements were immediately made to pump out the water, which took more than two days.

Later on that day, with soaked denims and a profound resolve to take action, we formalized the Salvage and Recovery Project, and began arrangements to get crates, people and the extensive and specialized equipment to successfully implement a time-sensitive disaster management project at this scale.

Down the Mine

“Jagger is gone, this is a construction site”

These were the words I heard on that first day that made it really sink in. I repeated these words during volunteer inductions to underscore the importance of safety, health and COVID compliance regulations, but in fact, the reality of our changed circumstances has taken time to sink in. Not only did we lose the Library, but we lost our workplace. I miss the quietude and peace of the Reading Room. I can still picture walking through it in my head.

On that first day, I donned a hard hat for the first time since 2008, when I went down 50 metres into a Mpumalanga coal mine as part of my postgraduate field research into the history of mining.

Eventually, the hard hat became our uniform. It also made it easy to tell who, on the campus, was involved in the project. The analogy of mining became ubiquitous among volunteers: the hard hats, the masks (to prevent inhalation of mould as well as to prevent the spread of COVID-19), the human chains. The heightened importance of safety, and the very real dangers involved.

I thought of George Orwell’s famed essay, Down the Mine. I couldn’t get the comparisons out of my head.

“when you go down a coal-mine it is important to try and get to the coal face when the ‘fillers’ are at work … At those times the place is like hell, or at any rate like my own mental picture of hell. Most of the things one imagines in hell are in there — heat, noise, confusion, darkness, foul air, and, above all, unbearably cramped space … it is so vitally necessary and yet so remote from our experience, so invisible, as it were, that we are capable of forgetting it as we forget the blood in our veins.”

George Orwell, Down the Mine

Here we were, extracting subterranean resources of the highest possible value to an academic institution. At its best, this shared goal inspired enormous camaraderie and mobilisation among volunteers. At its worst, the experience was exhausting, difficult and dangerous. It was, at times, my own (and others’) personal picture of hell in a library – but we bore witness, and never shied away.

I am still amazed how much was accomplished in such a short time. I wish to honour each person who contributed as best they could ‘down the mine’. I hope that this hidden experience of the workings of an archive and library, hidden from so many, and now brought to light, benefits our shared institutional understanding of the sheer physicality of a preservation library such as Special Collections.

For each person involved, their experience of the Salvage is unique. It involved multiple simultaneous processes, and it is remarkable how many took ownership of this. It was only through the collective contribution of an entire community that the salvage of Special Collections Library and Archive holdings was possible.

From Salvage to Recovery

There was little time to reflect on the ground. Days started very early and ended very late. Many asked me how I was. I realize now that I was frozen in an emotional sense; the urgency of the disaster, with its initial freneticism, confusion and exhaustion did not allow for this. At the time, I recalled the words of a great African writer, Es’kia Mphahlele, Down Second Avenue, which gave me great comfort:- (Notably, our copy of this book in the African Studies Library survived the fire.)

“…it is the lingering melody of a song that moves me more than the initial experience itself; it is the the lingering pain of a past insult that rankles and hurts me more than the insult itself. Too dumb to tell you how immensely this music or that play or this film moves me, I wait for the memory of the event.”

Es’kia Mphahlele, Down Second Avenue

Looking back, the Salvage was both a devastating and inspiring time, and in the months following the fire and the salvage, I have finally had time to grieve, to reflect and to prepare for the future.

What does Recovery look like?

Throughout the Salvage, we had to consider the longer-term Recovery phase. By June, Maitland House 2, an office block in Mowbray with generous space, was secured as an interim workplace where we could reconstitute not only the collections, but the workplace and structure required to run a preservation library and archive.

Unfortunately, soon after this, our capacity to move forward was hampered by the heightened state of national lockdown during the Third Wave of the Delta variant of the coronavirus. Our new premises were handed over as a clean slate, and in July we welcomed the staff to their new workplace.

However, there is much work to be done before we can resume as a functional department. Everything has had to be closely considered: implementation of ICTS infrastructure in a new space; measurements for new shelving and compactus that need to be purchased and installed; office spaces for each individual staff member; systems in place to facilitate the reconciliation of the collections; procurement of new book hoists, boxes, folders, packaging, scanners, photocopiers, microfilm readers, desks, computers; implementation of new safety and health measures. Fire drills.

The list is long.

We also had to tidy up after the Salvage – which has involved the cartage to new premises of all crates placed in different venues around the campus. At the time of writing, we have cleared all non-Libraries spaces, including classrooms in the A.C. Jordan building, particularly the English Common Room, as well as the Centre for African Studies Gallery and the Kaplan Centre.

All crates from these venues have been moved to Maitland House 2 and the University House dining hall, where the planned digitisation of AV archives will take place. The rest of the crates are still being kept in the Library Learning Lounge and Immelman 24/7 spaces, for now. Material in cold storage units on the Plaza are to be moved to off site cold storage.

We have been working with UCT’s Finance Department and Department of Alumni and Development to ensure that all funds donated to the university for the restoration of the Special Collections Department (previously housed in Jagger) are well utilised. We are also establishing a new, permanent Conservation Unit to serve the needs of the Recovery project, and all future conservation requirements of the Libraries and institution. The Jagger Salvage project shone a light on the dearth of expertise in this field in South Africa, and I hope that the Recovery will instil new understanding about the requirements of long- term preservation, especially in tandem with the demands of more contemporaneous priorities such as digitisation. With more than ten thousand individually wrapped and treated items in cold storage awaiting remedial conservation and restoration, as well as ongoing assessment of materials that were slowly and meticulously dried, the importance of professional conservation cannot be overstated.

The Recovery of Primary Collections

The Primary Collections team consists of highly skilled archival practitioners specialising in a range of repositories and formats – through professional training and years of acquired expertise, each of the archivists have intimate knowledge of the respective collections that fall under their portfolios.

The Primary Collections team also includes two dedicated Library Assistants whose portfolios and training have, up until now, focused on the application of preventative conservation. I am immensely proud to lead a team of such focused, committed and skilled practitioners.

The team has been busy working through the materials as they become accessible to audit what has been salvaged, account for what has been lost, and update our records accordingly.

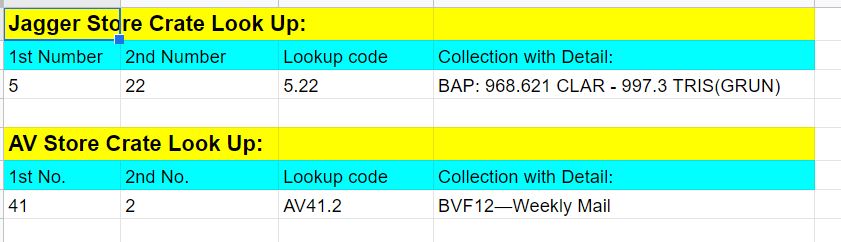

Mechanisms to support the Recovery include the application of the emergency crate-numbering system that was put in place during the Salvage. In particular, the preparation of the information captured in the copious hand written stock registers every day on site has facilitated recovery in many ways. A team of Libraries’ staff members, coordinated by Engela Britz, availed themselves to transcribe the stock registers in real time, to create a comprehensive database as a representative of our holdings in storage.

This task had to be done meticulously and timeously and its usage is manifold. In short, it gives us the ability to identify where collections were on the basement shelves, to physically group them in order, and to assess what is in any crate, especially if the items inside are not clearly labelled. We have been able to synthesize the emergency numbering system used within the stock registers with our own numbering of collections to create a digital ‘Crate Look-Up’ System.

One immediate application has helped us speed up the process of preparing metadata for the planned digitisation our entire Audio-Visual Repository (the first to be extracted from the flooded basement).

Salvaging the Blue Folders

One of the greatest losses to the archives is the destruction of most of its administrative records held in the Jagger Library Reading Room.

The records lost include the newly processed papers of previous University Librarians; original records of deposits and donations of books and papers; the original accession registry for the Manuscripts & Archives repository; the records of the African Studies Library, Manuscripts & Archives, and generally, records related to the history and evolution of UCT Libraries over nearly a century. This included papers showcased in a 2018 exhibition about the history of banned books at UCT Libraries. Recognizing this loss was immensely difficult, especially as the papers were in the process of being arranged, and thus kept in the Reading Room’s Archives Office.

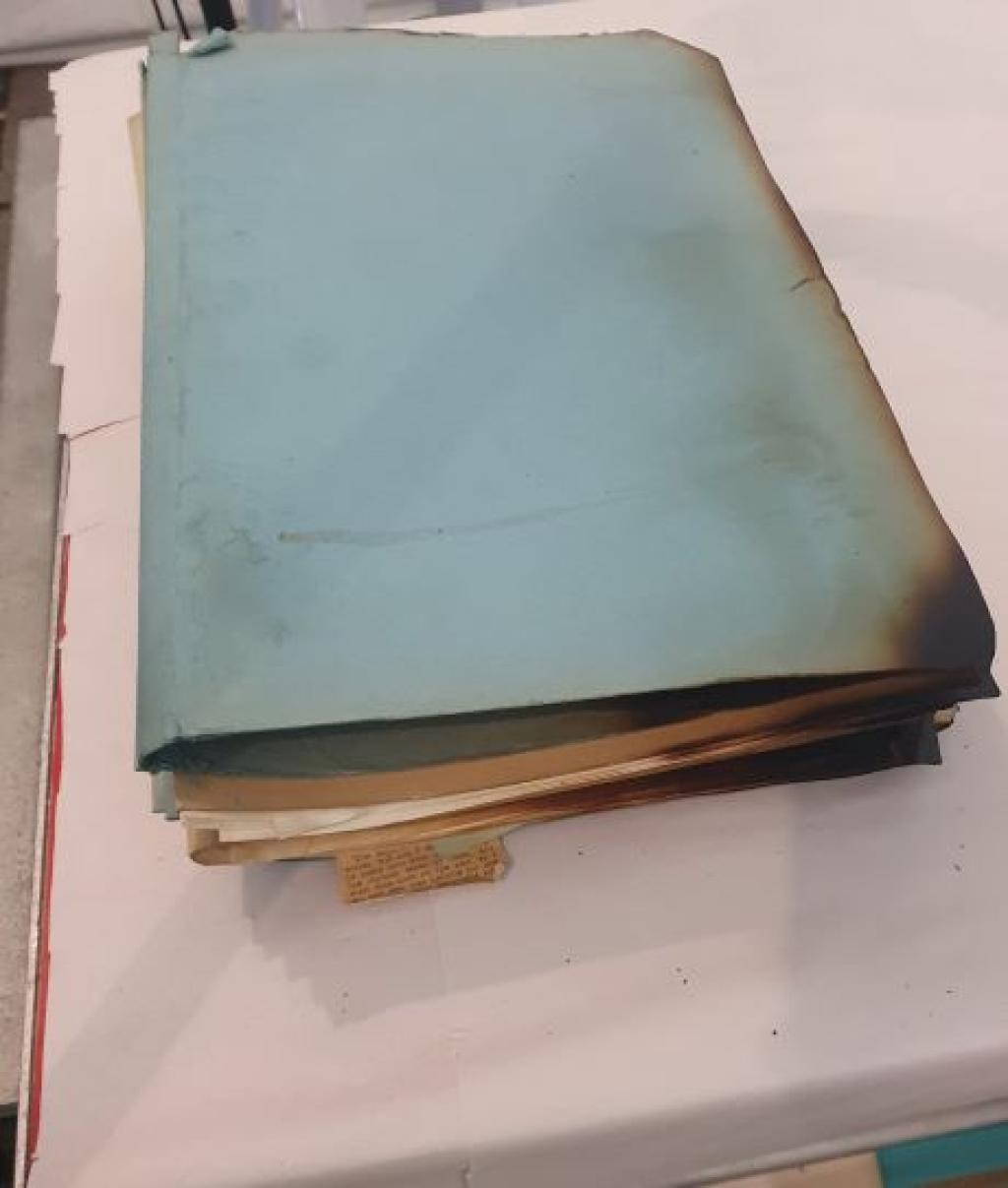

Perhaps most important to the provenance of the Archives was the record of deposit. Since 2018, the Primary Collections team has been involved in an overall audit of these paper-based records to develop a database in line with digitalising the administration of the archives. We dubbed this the ‘Blue Folders Project’ since all folders containing sensitive, often confidential information pertaining to deposit agreements, restrictions and wishes of depositors were kept in blue folders, as opposed to the buff or yellow folders with which researchers would be more familiar.

During the final week of the Salvage, we were finally able to assess what, if any, of the Blue Folders had survived. It turned out that several of the filing cabinets had withstood the flames, and the moment that Isipani Construction brought the remnants of this collection to the Triage area, my team soon took over the second triage tent, and became entirely devoted to dusting off the soot, replacing folders exposed to fire and damp, and then processing each set of files using the database-in-progress so that we could determine what we had lost and what we had salvaged.

Supporting depositors and researchers

Since the fire, we have received hundreds of emails requesting updates on specific collections. Each request has been logged into a database to facilitate our responses when possible. Given the myriad challenges of recovery, this has not been possible yet in most cases. The team is embarking on a process to reconstitute collections. Once we have done this, we will contact depositors directly. Once depositors have been informed, the losses will be publicly shared.

For regular users of the Jagger Library, the loss of the physical space for study and research has been devastating, and the Libraries have worked tirelessly to provide alternative access to resources. We recognize this cannot make up for the inaccessibility of these records. Wherever possible, we are still able to provide digital transfers of materials.

We hope to re-introduce reference services in early 2022 for collections not affected by the fire.

Set up during the lockdown, we are also maintaining a log of all research requests and will provide feedback and support when possible.

If you wish to follow up about a specific collection, or request support for access to materials, please contact lib-jagger@uct.ac.za or Ask-a-Librarian.

Further references

Monique Mortlock from ENCA reported closely on the fire.

UCT Libraries’ Executive Director interviewed on SABC, 21 April 2021

Nikki Crowster, Libraries Director and Jagger Salvage and Recovery Lead (and my very own rock during this time), interviewed on eNCA, 2 May 2021.